Juvenile Bowhead Whale off Baffin Island

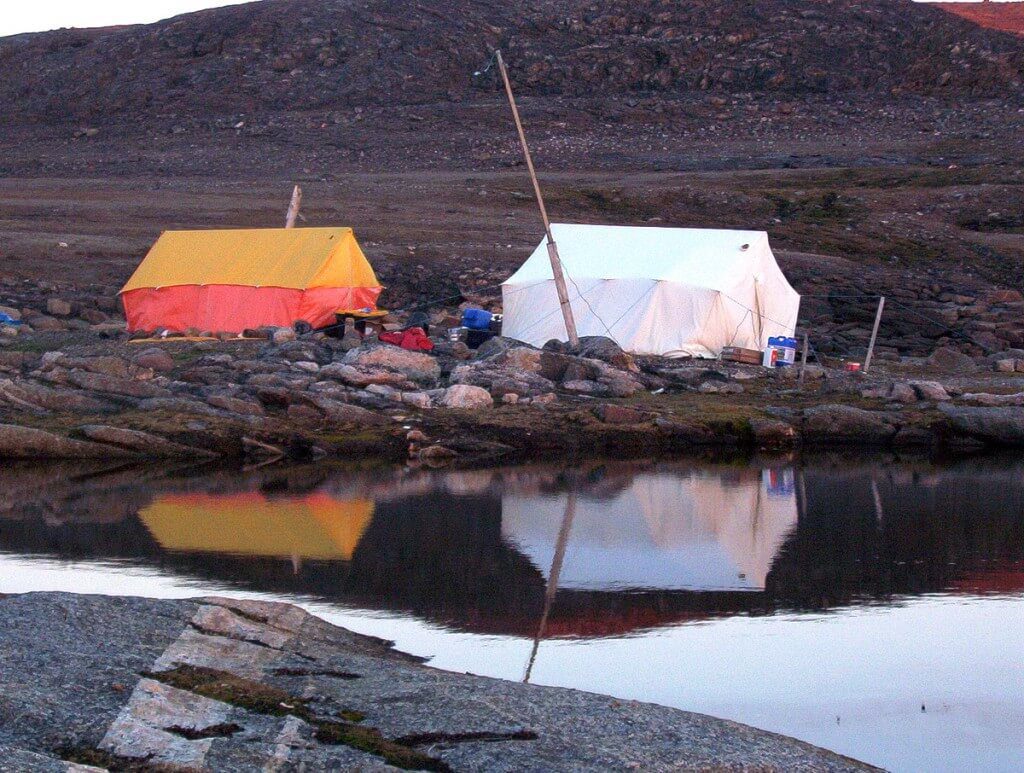

An early dawn found a grey sky with the waters of the Arctic Ocean sitting at low tide below our base camp on Kekerten Island, off Baffin Island.

After a quick breakfast, one of our Inuit guides invited us to accompany him to a vantage point on a hilltop from which it would be possible to look for whales out on the ocean.

The hilltop we hiked to is in the top right corner of my photograph, and from that perch, we hoped to spot Bowhead Whales swimming in the channel on the left. The channel in the Inuit language is called “Tenudiackbik”, a legendary waterway where, up until the 1900’s, its waters teamed with Bowhead Whales. Today, as we would soon learn, it’s a tough job to spot any of these creatures.

This is a drawing of what a Bowhead Whale looks like. It has a massive body with blubber 2 feet thick underlying the skin to protect it from the icy waters of the Arctic. Most Bowhead Whales average from 50 to 60 feet long (11.6m), but they have been seen as long as 70 feet. Most of us think of “there she blows” when we think of whales. That “blow” comes out of its nostril, which is called the “stack”. The stack is the bump at the top of its head.

With binoculars in hand, everyone began scanning the waters for any telltale signs of Bowhead Whales.

The Inuit informed us that Bowhead Whales migrate every spring from Greenland across to Canadian waters, heading west to the bays along Baffin Island. It is in those bays that the whale mothers give birth and then set up a form of communal nursery to take care of their newborn calves.

One of the first things we spotted was an iceberg on the far side of the channel.

I took a quick break from the glare of the sun off the water’s surface.

As I soon learned, spotting whales is not an easy task. The number one rule according to Inuit guide, Solomon, is to scan the ocean’s surface from left to right and to watch for any unusual movement. He told us that, with luck, we might be able to spot a water spout which can reach 14 feet into the air. But even with his input, he still beat us to the punch, soon spotting and pointing out the first Bowhead Whale of the day.

One of the things Solomon spotted were the telltale signs of air bubbles left behind by a whale as it swam beneath the surface. These bubble markings would prove very useful in helping us to track the whales’ movements.

Levy, our Inuit helmsman, followed the air bubbles for a short distance and then decided to head off blindly to a location far across the waters. We all just sat their for 20 minutes, with no whale bubbles around us, and then suddenly a Bowhead Whale broke the surface right beside our boat. This Inuit skill and knowledge would be put to use many times in the coming days.

In the middle of the afternoon, a juvenile Bowhead Whale took some interest in our presence there in its waters. Levy figured the young whale was around 9 to 12 months old, and through the water, it appeared to be 11 to 18 feet long. Like most young, it was curious about we interlopers.

The juvenile Bowhead Whale even lifted its head out of the water for a peak.

Soon afterwards, the baby Bowhead Whale, along with the rest of the whale pack, headed off towards a bay further along the shore of Baffin Island.

With our day drawing to an end, the Inuit guided our boats back to the base camp on Kekerten Island where we were treated to a meal of freshly-caught Arctic Char.

While we southerners ate our fish cooked, the Inuit guides prepared and ate their fish raw in the traditional Inuit way.

After a long day at sea, and with the sun attempting to set in the Land of the Midnight Sun, we called it a day.