Common Snapping Turtle hatchlings on the Nokiidaa Trail in Ontario

Common Snapping Turtle hatchlings on the Nokiidaa Trail in Ontario

Early last fall, Bob and I wanted to introduce my sister and brother-in-law to a new trail system that we discovered earlier this year. It is called the Nokiidaa Trail, which in Ojibwa means “walking together”. The trail which links between the towns of Aurora, Newmarket, and East Gwillimbury is used by cyclists as well as walkers, and we were on wheels on this particular day. Well into our ride, I spotted something round and dark on the crushed rock surface of the bicycle trail, and nearly ran over what turned out to be a baby Common Snapping Turtle (Chelydra serpentina). In the immediate vicinity, we discovered four others lingering on the path.

We were cycling the section from St. John’s Sideroad in Aurora, north through Newmarket and beyond. It is a highly interesting trail to walk or cycle because sections pass through forests, meadows and wetlands, as well as skirt town parks and green spaces. It is nice that the trail follows the East Holland River, which in this picture is just to the left of the trail about a distance of 50 feet (15 m) down a moderately-sloped bank. It was here on the trail where we found the turtles.

For comparison, this is an adult Snapping Turtle that was discovered at my parents’ beach at Oxtongue Lake two summers ago. If you have ever seen an adult Snapping Turtle in person, you know that these large members of the Chelydridae family are quite fierce and look intimidating with their powerful beak-like jaws and snake-like head and neck. On top of that, their heads are large and their snouts are short.

These reptiles have remained largely unchanged since the prehistoric era, and even the hatchlings have a generally dinosaur-like appearance. Even so, this baby Snapper seemed quite cute and vulnerable which is in keeping with Snapping Turtles’ timid behaviour in water where they are quick to swim away from humans.

An adult Snapping Turtle is quite a formidable reptile with sharp claws, a neck that can extend backwards over two-thirds the length of its shell, and a spiked tail that is as long as or longer than the upper carapace or shell. This is another adult Snapping Turtle that Bob and I spotted along the sandy bank of the Oxtongue River below Ragged Falls. Perhaps it was looking for a place to lay its eggs since they seek out a sandy, dry location wherein to dig a hole.

This baby Snapping Turtle definitely had pointed claws on its little feet, but the sharp, saw-toothed keels along the ridge of the tail had not developed yet. We had a good look at the hard plate that covers the stomach, the plastron, but those of Snapping Turtles are small and leave a good portion of their body exposed.

Snapping Turtles get their name because, when on land, they snap and hiss at any potential threat instead of withdrawing into their shell. Unlike other turtle species, Snapping Turtles are unable to fully retract their head and legs into their shell for protection because their plastron, lower shell, is too small to accommodate their whole body. Therefore, they put on a vicious display to scare off predators. And these prehistoric-looking reptiles can inflict serious injury if they need to defend themselves.

Bob put down a 2-dollar coin to demonstrate the size of this hatchling. Judging by its size, these young turtles had only recently emerged from the eggs because they begin life about the size of a quarter. It is customary for Snapping Turtle eggs to hatch in late September or early October, so these hatchlings were just a few days old. The shell of an adult Snapping Turtle can grow to a length of 50 centimetres (20 in.), which adds a lot of weight to the turtle’s body. Considering that an adult Snapper can achieve a significant weight, anywhere between 4.5-32 kilograms (9.9-70 lb.), this little one has a lot of growing to do.

It was a mere 20 or 30 feet further along the cycling trail that my brother-in-law spotted the next three hatchlings, so we gathered them up and put them together in a group. Next, we scoured the stretch of bicycle trail behind and in front of us to see if any other young turtles were at risk of being run over by inattentive cyclists. A female Snapping Turtle usually lays a clutch of 25 to 80 eggs, so there was a good chance that other hatchlings were nearby, but if so, they were well hidden or had already made their way to the river.

My sister and I were quite enamored with these recent hatchlings, which, like adult Snapping Turtles, were very slow and vulnerable when moving on land. Adult Snappers have few predators, but delicate baby Snapping Turtles and even juveniles are eaten by a variety of predators that include herons, crows, large fish, bitterns, bullfrogs, raccoons, snakes, hawks and even larger turtles.

Even baby Snapping Turtles construe the essence of their prehistoric past with their rough, sculptured shells. A hatchling is darker than an adult, three pronounced ridges or keels run the length of its carapace, and the shell is rougher and more sculptured than that of an older turtle.

The carapace of an adult Snapping Turtle is almost perfectly smooth, and grows smoother as a turtle ages, although there is apt to be algae growing on it from the extended periods spent living in water. Often, if viewed from above, a Snapping Turtle can be mistaken for an underwater rock.

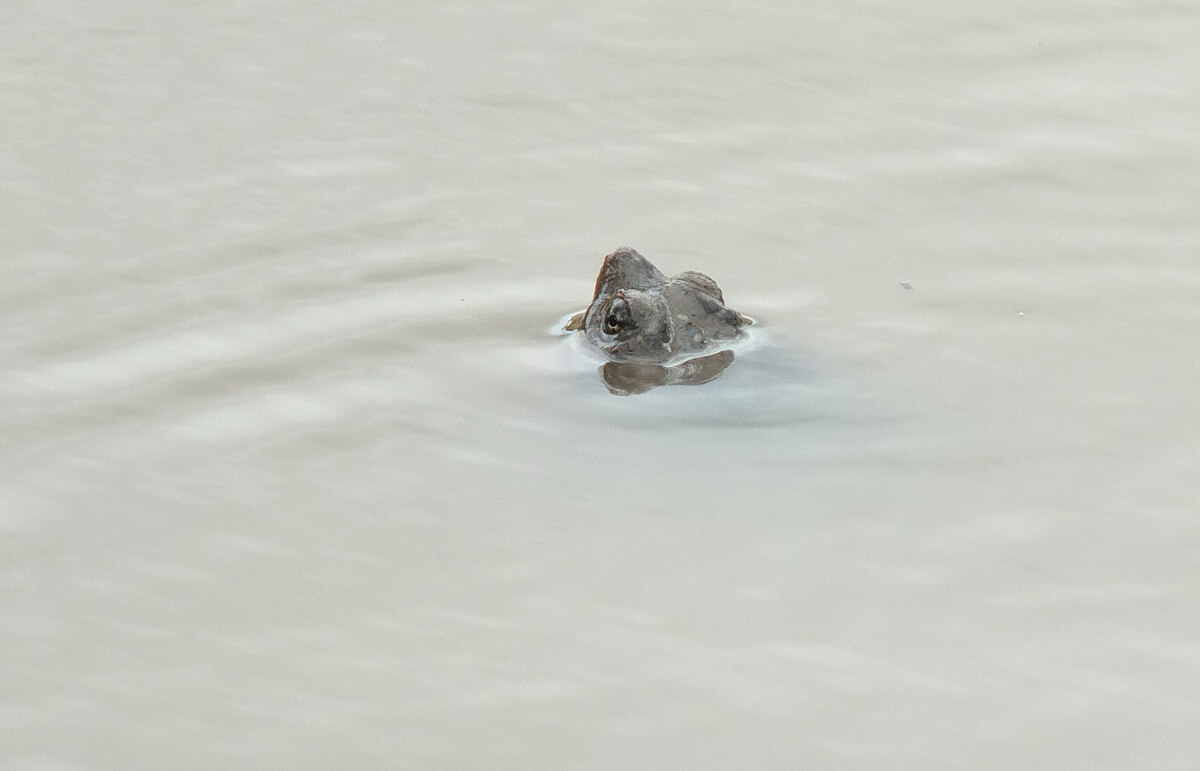

Often, all that is visible of an adult Snapping Turtle is its snout poking gently above the water’s surface. These majestic, ancient-looking creatures have inhabited streams, rivers, ponds and wetland areas for millions of years. They prefer shallow bodies of water where it is possible to hide beneath leaf litter, submerged brush or logs, and they use their long neck to reach the surface for an occasional breath of fresh air.

Alternately, slow-moving rivers and streams with soft, muddy bottoms provide perfect habitat for Snapping Turtles. They can burrow into the mud and remain with only their nose exposed above the surface. Two nostrils are located at the very tip of the snout and function as snorkels. Bob and I located this huge Snapping Turtle in July, 2013, on the Green River in Markham, Ontario, just above the Whitevale Dam where the river has backed up to create a small wetland adjacent to the flowing water. We observed its movements through the murky water, but at no point did the turtle climb out on shore.

It is rare that a Common Snapping Turtle will be observed basking in the sun while floating on the surface of the water with only its carapace exposed, but that is just what Bob and I witnessed when hiking in the Hendrie Valley in Burlington this past April. While in the process of photographing some Wood Ducks, Bob noticed this monstrous bulk of fleshy matter moving in one of the ponds off Grindstone Creek. Only for the distinct contours of the Snapping Turtle’s shell were we able to identify the creature. The view gave insight into the characteristics of the ventral side (underside) of a Snapping Turtle. It is delicate and soft and ranges in colour from yellowish to light brown, and sometimes, as in this case, with a reddish tinge. The turtle maneuvered itself lethargically from one area of the pond to another because this species of turtle does not swim very well, but maintained its shell above the surface to absorb the weak rays of the early spring sunshine.

There are only two species of turtles found in North America that belong to the Chelydridae family with the other being the Alligator Snapping Turtle, but Common Snapping Turtles are usually the largest and heaviest of the native freshwater species. These gentle giants can live to be 100 years old, and although they continue to grow throughout their lives, growth slows with age. Like a tree, rings on the shell of a Snapping Turtle can be counted to determine the creature’s age.

Getting back to the baby Snapping Turtles that we rescued along the Nokiidaa Trail in Aurora, the four of us made a decision to remove the hatchlings to the safety of the river where they appeared to be headed in the first place. We were just going to speed their progress. Despite one of our group having slipped on the greasy mud at the river’s edge and almost gone for his own swim, all five turtles were safely placed on the leaf litter at the shoreline.

It was gratifying to know that this population of Snapping Turtles will go a long way to keeping the water clean in this river. About ninety percent of a Snapping Turtle’s diet is made up of dead animal and plant matter. We felt good about assisting the defenseless offspring, and after watching them swim off, we carefully climbed back up the wet riverbank and remounted our bikes. These baby Snapping Turtles were the highlight of this bike trip.

You May Also Like:

Eastern Garter Snakes Basking In Thickson’s Woods in Whitby

A Northern Whiptail Lizard at Grand Canyon National Park

A Yellow-backed Spiny Lizard at the Grand Canyon, Arizona

Our South African Journey to Kruger National Park

Visiting Machu Picchu, Our long time dream