Frame To Frame – Bob and Jean

California Condors At Grand Canyon National Park

When Bob and I visited Grand Canyon National Park , our primary objective was to revel at the overwhelming and impressive scale of the canyon. Little did we know that our passion for birdwatching would be so richly rewarded both on the South Rim and deep within the canyon, itself. On one visit to Hopi Point, we were lucky enough to spot one of the two California Condors known to be nesting in a nearby rock face.

On our first full day at Grand Canyon National Park, Bob and I started off with an early-morning helicopter flight over the canyon, but once back at our lodgings, we set off to explore the South Rim by taking advantage of the free bus service operated within the Park. En route to Hermit’s Rest at the furthest end of Hermit Road, the bus stops at several look-off points.

Fantastic views of the Grand Canyon can be had from all of the lookouts along the South Rim as well as from any point on the walking trails in between those lookouts. For the most part, no barriers exist, so visitors are responsible for their own safety. Bob was keen to get an unimpeded view of the gaping canyon when he ventured out on one outcrop.

At some points, the Colorado River is visible from the South Rim, but coursing along the bottom of the Grand Canyon, approximately 7,000 feet below, it appears like a small stream.

Bob and I opted to disembark at Hopi Point because the condors are often sighted soaring over the canyon there.

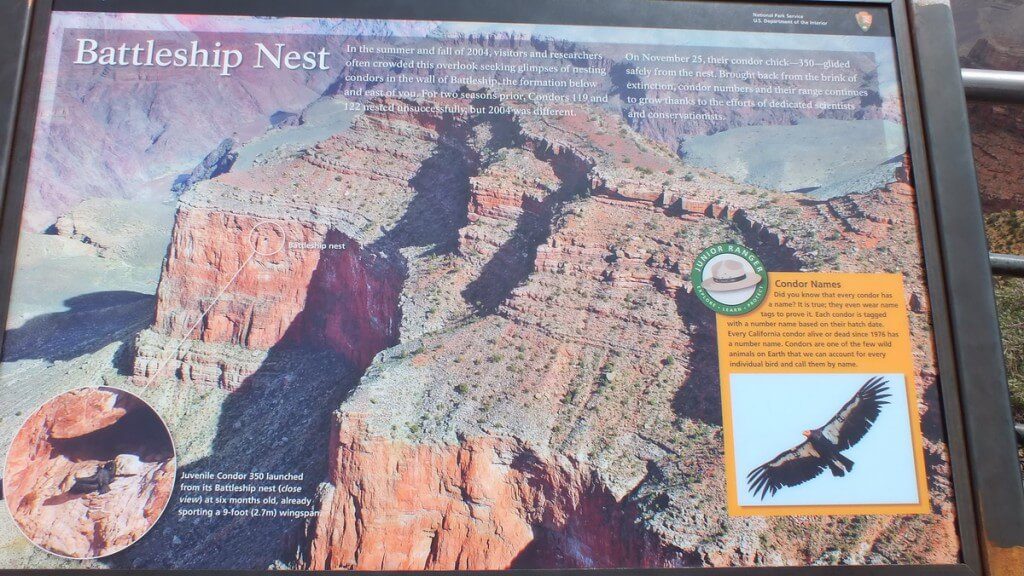

From Hopi Point, a fantastic overlook of Battleship Rock (the stately formation of red rock in the centre of this photo) provided the backdrop for our observations. Even though it was midday, we were hoping to catch a view of one, if not the two, condors flying over the area.

A sign that has been erected by the Park Authority details the location of the present condors’ nest cave, which happens to be into the side of Battleship Rock. It is referred to as Battleship Cave.

Grand Canyon National Park operates numerous free programs given by park rangers and volunteers, and one of those programs is the Ranger on the Rim: California Condor talk. It takes place at Hopi Point, but we were too early this day to catch the Ranger on duty.

So, Bob and I put our own observation skills to use, and with the help of our binoculars were able to spot the opening of the condors’ nest cave near the top of one face of Battleship Rock. It is the small black spot just to the left of centre of this photograph.

This nest cave has been used by condors for over 10,000 years, verified by scientists who found fossilized egg shells within the cave. Looking at the mouth of the nest cave from as far away as Hopi Point, we had no idea the size of the opening, let alone what we were really capturing in our picture.

We subsequently learned that the condors’ nest cave is 5 feet wide by 7 feet high by 34 feet deep, opening up into 2 chambers at the back of the cavern. A white rock sits at the mouth of the cave, and it was only later that I realized I had captured an image of one of the adult condors sitting in front of that rock. I was thrilled!

In addition to that, we were also lucky enough to pinpoint one of the adult condors soaring in close proximity to Battleship Rock. This is a big deal because California Condors are one of the rarest birds in the world. It may look small in our photos but the condor is the largest land bird in North America with a wingspan of up to 9 1/2 feet. A condor can weigh up to 23 pounds.

Condors rarely flap their wings, except during takeoff and landing, but they are superb gliders that can cover 100 miles or more in a day. Because condors use thermal updrafts, they expend little energy while soaring and gliding at speeds up to 50 miles per hour.

What made our condor sighting so exciting is that, back in 1987, California Condors became extinct in the wild. The 22 remaining wild condors were captured at that time, and captive breeding programs initiated to help increase their numbers and save the species.

Beginning in 1991, the reintroduction of California Condors into the wild began in such places as the Grand Canyon. As of May 2012, there were 405 known condors living, of which 226 exist in the wild. The fact that they were saved from extinction made our condor sighting very memorable and meaningful.

A few days after our first visit to Hopi Point, Bob and I found ourselves once again on the trail heading towards Hermit’s Rest. We had rented bicycles for a few hours in order to speed our movement along the South Rim Trails, but the 100-degree temperatures required us to pace our exertions and take frequent stops.

We had timed up our bicycle ride so as to catch the interpretive talk about the California Condors at Hopi Point. It so happened that the volunteer ranger, Gabby, had a telescopic lens sighted on the condors’ nest cave, and it is when I saw the gaping entrance to the cave through the telescope, I realized that a large white rock sits on the doorstep of the cave. I knew, at that moment, that the black object at the mouth of the cave, in my own photograph, was one of the condors sitting in front of that rock!

Gabby also had at her disposal an audio listening device or directional microphone. The two condors nesting in Battleship Cave, as are all California Condors, are banded with numbered tags that include a transmitter. It is important to be able to track the birds and distinguish one from the other.

Using her listening device, Gabby allowed us to hear the beep of the transmitter on the male condor, which at that moment was resting comfortably within the cool shady confines of the dark nest cave chamber. He was busy tending the one young condor that had hatched around April 30, 2013.

In our video, you get a chance to hear the beep of the male condor.

The tag on the female condor has a separate distinctive beep, and at that moment, the beep was not registering on the microphone. Gabby said that the female condor was out of range, probably off scavenging in the canyon beyond the immediate area.

Gabby imparted lots of interesting information to Bob and me, like the fact that the nest cave is presently being used by Condor #234 (Tag 4), the adult male, and Condor #280 (Tag 80), the adult female, seen here copulating. This spring, Gabby had the good fortune to see this pair copulating, after which they did a pair’s flight…a side-by-side flight with the tips of their primary feathers touching. She expressed that the ritual was “really romantic”. (Photo courtesy of Grand Canyon Files)

Condors breed only once every two years and produce only one egg. Adult condors are monogamous and pair for life, both sharing in the incubation of the egg and feeding of the offspring until it can find food on its own. Surprisingly, that could take up to one year. At Battleship Rock, the condors’ egg was laid around March 4, 2013, and, at two days old, would have looked like the chick we see here. (Photo Courtesy of Grand Canyon Files)

A short 36 days later, the hatched chick is a grey fluff ball about the size of a basketball. When we visited Hopi Point, the chick in the cave would have been approximately this size and no longer required constant care. It will fledge in October or November but will remain with the adults into the second year of its life. (Photo Courtesy of Grand Canyon Files)

So, to say the least, Bob and I were ecstatic to have seen the adult condors if even at a great distance. With the continuing success of the reintroduction program and survival of those condors now in the wild, hopefully one day, future generations will see California Condors soaring all over their native range…from British Columbia, Canada, to Baja, California on the West Coast, and from New York to Florida on the East Coast. Now, that would be awesome if excessively hopeful.

California condors became endangered the first time, because they were ingesting lead ammunition, from the prey they were scavenging on. They were captive bred, and reintroduced back into the wild again. But their numbers are declining now, because of lead ammunition.

Thank you for your comments. It is true that lead poisoning from ingesting fragments of lead ammunition found in the carcasses they feed on is, today, the biggest threat to their survival. Decades ago, egg collecting, accidental poisoning from cyanide-laced bait in coyote traps, and general habitat degradation contributed immensely to their declining numbers, not to mention farmers who shot them because they thought that the condors were killing their sheep or cattle. In fact, condors are scavengers, and only eat dead animals. I am glad that efforts are being made to educate the public on how best to assist in the survival of the California Condors.

When they feed on a deer carcass, when deer die naturally, they head off to a thicket of vegetation and die. So if a deer is shot, and the hunter does not fetch the carcass, the California condor will feed on it, and ingest the lead bullet that killed it.