Exploring The Cliff Dwellings At Mesa Verde National Park

It was becoming a habit, it seemed, for Bob and me to wake up between 6-6:30 a.m., and the day following our hike on the Bright Angel Trail was no different. Because our leg muscles were way too spent for any other activity, our intentions were to drive across Arizona into Colorado to Mesa Verde National Park. Once there, we were absolutely in awe of the excellent examples of preserved and protected cliff dwellings once used by Pueblo people.

We found ourselves on the road that morning by 7:45 a.m. and wasted no time driving the first section of the route since we had covered it a couple of days earlier when going to the North Rim. East of Tuba City, the panoramic views of the desert were constantly shifting, like the sands themselves. The most unusual land formations fascinated us with their tight folds of rock, smooth, rounded surfaces, geometric shapes, or flattened tops. In one area, red cliffs spawned jagged red teeth referred to as “baby rocks”. The landscape was so inhospitable as to appear uninhabitable.

Still, oases popped up in unexpected locations providing a lush green contrast to the monotony of monochromatic desert sand and rock. Communities seemed to thrive near those meager water sources even though, in most cases, no water could be seen in the marked “washes” (creeks) or rivers.

In other cases, people chose to live in the most austere locations, like tucked at the base of rugged mesas and barren cliffs.

Four Corners is where we exited Arizona, drove across a corner of New Mexico and on into Colorado. Four Corners is so named because a corner of Utah also meets the borders of the other three states there.

In Colorado, as we drove to a higher elevation, not only did the vegetation change but the terrain became more mountainous. The San Juan Mountains formed a formidable range bordering the roadside flatlands both of which were amply populated with trees. There was also more evidence of farming in the presence of flocks of sheep and the occasional fence holding back cattle or horses.

It was quite evident as we neared Mesa Verde National Park as to where the Park got its name. Mesa Verde is Spanish for Green Table and refers to the monolithic flat forested mesa that dominates the landscape in that region.

It was necessary to complete a steep ascent up and around the soaring mesa, about 20 miles by car, but at designated points, there were lookouts and trailheads for hikes to scenic locations.

The drive took us to Chapin Mesa Archeological Museum perched at the edge of a very deep, gaping canyon.

From there, Bob and I descended a short, winding trail below the lip of the canyon to reach Mesa Verde’s best-preserved cliff dwellings.

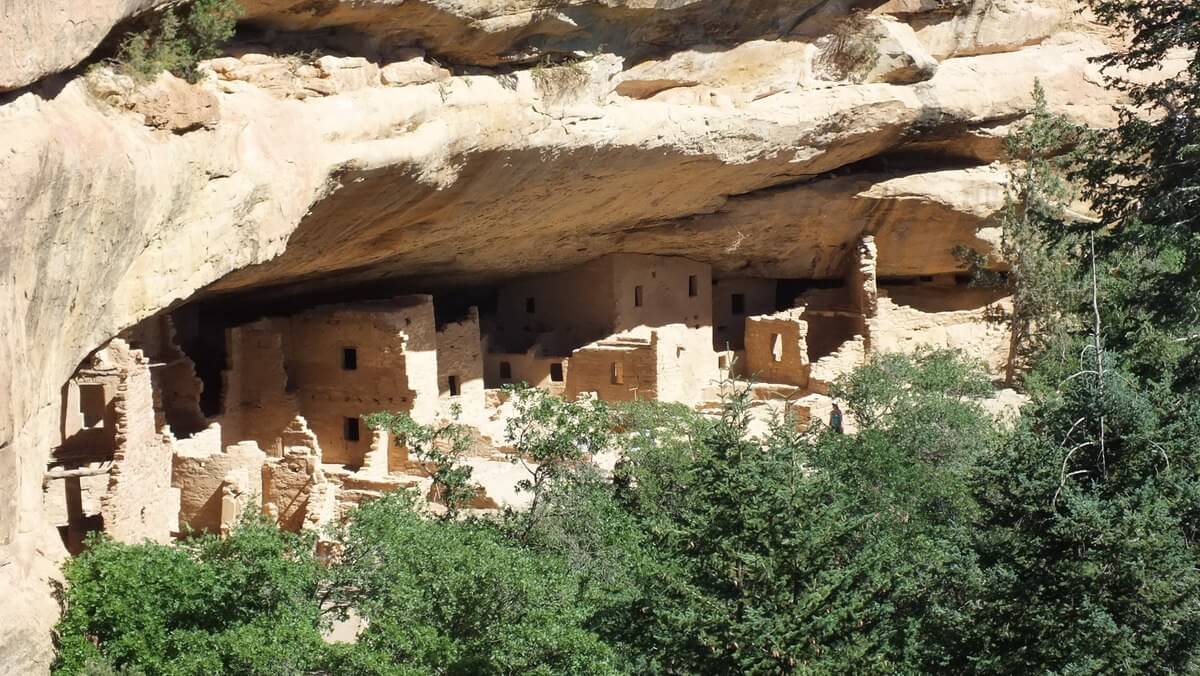

As we navigated the quarter-mile (0.4 km) descent, intriguing glimpses of Spruce Tree House heightened our expectations. Tucked into a natural alcove below the mesa’s surface, the ancient village was well protected from the elements, would have provided for ease of defense, and remained completely hidden from enemies or intruders above.

The paved trail into the canyon represented a mere 100-foot (30-m) descent that transported Bob and me back through time the nearer we got to the once humble lodgings of the Pueblo People. It is these structures built within caves and under outcroppings in the canyon cliffs that has gained historical significance for Mesa Verde National Park. Within the Park there are over 4,500 archeological sites of which 600 are cliff dwellings such as Spruce Tree House.

The first Ancestral Puebloans settled in Mesa Verde over 1,400 years ago, and at that time, they were referred to as Basketweavers for their skill at the craft. They were primarily nomadic hunters and gatherers. Beginning in about 550, they chose to lead a more settled way of life and turned to farming on the mesa tops where the soil was fertile and well watered. Small villages sprung up, but their dwellings consisted of simple pithouses that featured a living room sunk a few feet into the ground. Four corner timbers supported the roof, and there was a deflector for a firepit.

Archeologists originally called the indigenous people Anasazi, the Navajo word meaning “ancient foreigners”, but by 750, the Anasazi descendants advanced from living in Pithouses to above-ground houses that featured upright walls of pole-and-mud construction. The new style of houses were built one against another in long, curving rows hence creating small villages on the mesa tops. From then on, the people of this ancient culture became known as Pueblos, a Spanish word meaning “village dwellers”. Often a pithouse or two was kept in front of the adobe houses, and those eventually evolved into kivas.

Along about 1000, the people of Mesa Verde advanced from adobe construction using poles, mud, grass and clay to skillful stone masonry. In their mesa-top villages, walls of thick, double-coursed stone rose two and three stories high and were joined together into units of 50 rooms or more. For about 100 years, the Pueblo population flourished and grew to several thousand that were concentrated in compact villages, often with the kivas built inside the enclosing walls rather than out in the open. It was their fine masonry skills that were later employed to transform cliff alcoves into villages such as Spruce Tree House, the third largest of the cliff dwellings at Mesa Verde. Constructed around 1190, it probably housed 60-80 people in a total of 130 rooms and 8 kivas.

At Spruce Tree House, there are several examples of kivas. These chambers that evolved from earlier pithouses assumed a new role in the villages as gathering places and ceremonial rooms. In addition to a firepit, each kiva had a sipapu which was a hole provided for passage to the underworld from which the people believed they had come, and there was likely an antechamber for storage bins or pits.

As Bob and I walked towards the center of the village, all that could be seen of one kiva was a ladder sticking up through a hole in the ground. Although we had a good view into the kiva from above, we both climbed down the ladder into its recesses. In their second incarnation, Pithouses were used much as a church would be. In fact, Kiva is the Hopi word for ceremonial room, and it is believed that the Puebloans used these subterranean spaces for healing rites or to pray for rain, luck at hunting, or a good crop.

As we descended the ladder, it was possible to see the well-formed and artful construction of the kiva. Pilasters support a beam-and-mud roof with only one central hole for the ladder, so we had to wait our turn before climbing down into the cool interior. With the sunshine streaming in, the space seemed larger and more airy than I expected. It is no wonder that Kivas were also used as gathering places for such activities as weaving.

Several kivas exist within each grouping of houses so that every clan living at a certain site had its own large, round chamber complete with a ventilator, bench, air deflector, fire pit, pilasters and a sipapu, the symbolic entrance to the underworld.

Back above ground in Spruce Tree Village, Bob and I marveled at how the builders fit the structures to the available space within the alcove on the cliff face. These more sophisticated structures incorporated adobe bricks of sun-baked mud and sandstone. Most walls were single courses of stone, perhaps because alcove roofs limited heights and yet protected the walls from erosion by the weather. Many rooms were plastered on the inside and decorated with painted designs.

Architecturally, from one village to another, there is no standard ground plan, and rough construction is sometimes found alongside walls of well-shaped stones . In rare cases, a one-room house will stand alone, while in others, villages such as Spruce Tree House and Cliff Palace,the largest grouping of dwellings at Mesa Verde, has 150 rooms joined together.

What an amazing feat to carve the stacked chambers, tall, straight walls and towers into the irregularly-shaped recesses of the sheer rock faces. The stone walls of the large pueblos are regarded as the finest ever built in Mesa Verde, with their straight courses of carefully-shaped stones. They have withstood the passage of time, a testament to the skill and ingenuity of the Puebloans who only had available to them tools made from local trees, plants, animals and stone to complete all of their tasks.

From this bird’s eye view of Spruce Tree House, it is very apparent how secure the location would have been from intruders. In many cases, the Anasazi reached their mesa-top fields by hand-and-toe hold trails chipped into the canyon walls. Farming had replaced hunting and gathering, the Basketweavers’ main livelihood, but the Pueblos still supplemented crops of beans, corn and squash by gathering wild plants and hunting. Rather than using an atlatl, a spear thrower, they became accomplished with the newly-acquired bow and arrow. Their skill at basket weaving was all but replaced when they learned to make pottery.

As Bob and I contemplated the hard life that the Mesa Verde people lived, the structures spoke to us with a certain eloquence. Though no written records ever existed and much that was important in their lives has perished, the cliff dwellings tell of a people adept at building, artistic in their crafts and expert at eking out a living in a difficult land.

The Puebloan people selected appropriate sites for their cliff dwellings all along the deep canyons that cut through the mesa in Montezuma Valley. Bob and I had to drive further up the mesa for a view of Cliff Palace, the largest ancestral Puebloan cliff dwelling found anywhere.

From a lookout perched at the lip of the canyon, we had an excellent view of the dwellings in the opposing cliff face, and as luck had it, the ruins were vacant at the time. A tour group was assembling for the descent into the gorge, and our perspective gave us a real understanding and appreciation for the intricate construction of the dwellings.

Cliff Palace was less protected by a narrower overhang, allowing for more deterioration over the centuries, but the wider and longer ledge allowed for a larger village. It includes everything from lookout or signaling towers to 4-storey houses, open courtyards, and like Spruce Tree House, isolated rooms in the rear and on the upper levels for storing crops. Although a lot of knowledge gained about the Puebloan people was acquired from refuse thrown over the slope in front of their homes, the Puebloans did allow for temporary storage of refuse behind the dwellings, as well.

The location and symmetry of the dwellings reinforces how important architecture was to the Pueblo People. Their knowledge and traditions were handed down from one generation to the next, and by the Classic Period, from 1100 to 1300, the Mesa Verde people were heirs of a vigorous civilization whose accomplishments in community living and the arts have been ranked among the finest expressions of human culture in North America.

The kivas at Cliff Palace are not as well preserved as at Spruce Tree House with most of them having no roof. This kiva was accessed by a ladder that leads up the side of the wall encircling its entrance.

As well as a clan having access to its own kiva, they also had rights to their own agricultural plots on the mesa top or in the valley below their dwellings.

From one village of cliff dwellings to another, there is some variation in the makeup of the adobe bricks and mortar, depending on the natural materials available. The basic construction material was sandstone that was shaped into rectangular blocks about the size of a loaf of bread, although limestone bricks were also used. The bricks were held together and plastered with adobe mortar, a mix of dirt and water.

The prehistoric villages at Mesa Verde National park provide a spectacular look into the lives of the Ancestral Pueblo people. They lived in these amazing cliff dwellings for almost 100 years, but, for whatever reason, drought, crop failures, or depletion of soil, forests or animals, the people abandoned Mesa Verde starting in 1270. Maybe even social or political problems began to surface within the aggregated social structure, but by 1300, Mesa Verde was deserted. Their population traveled south into present-day New Mexico and Arizona where they settled with kin who had already established there.

With a plan to get back to Monument Valley in time to see the sunset, Bob and I put the pedal to the metal for our return trip across Colorado into Arizona. No time was wasted in order to achieve our goal. The time was tight, but traffic was light, an earlier construction site was shut down for the day, and our tank was full. Four Corners, here we come!

Frame To Frame – Bob and Jean