Our Birding Trip In the Mangrove Swamp near San Blas

In our quest to see and photograph as many different species of tropical birds as possible while visiting San Blas, one of the best locations in all of Mexico for birding, a boat tour into the mangrove swamps was a must-do activity for Bob and me. And what could be more perfect than a languid birding boat trip through La Tovara National Park, a federally protected ecological preserve?

On our first morning in San Blas, at the recommendation of Josefina at Hotel Garza Canela where we were staying, we hired a knowledgeable guide, Chencho, to take us on a birding trip through the San Cristobal mangrove estuary and deep into the mangrove swamps. The tour would cost 800 pesos ($80) and was booked for a 3 p.m. start.

Our guided birding tour began near the El Conchal Bridge at the edge of town and proceeded first toward the mouth of the San Cristobal River where it joins the Pacific Ocean.

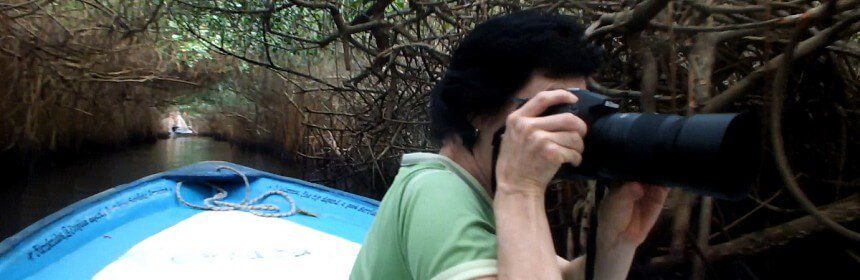

Chencho’s given name is Jose Inocencio Banuelos, but for simplicity’s sake, he goes by the nickname Chencho. He is a skilled boatman and birding guide so with him at the helm, Bob and I had every hope of finding the must-see birds along our route. The afternoon was hot, but we had come prepared for the chilly temperatures that would creep into the mangrove swamps once the sun set.

As we motored toward the El Conchal Estuary, that large open area where the river’s current meets the sea’s tide, exposed mud flats along the river’s edge testified to the low tide at our outset. These mud flats soon revealed a good number of bird species that had come to forage in the brackish water and soft sediment.

One of the first birds to catch our eye was a Tri-coloured Heron…

another of which kept vigil on a mound of rocks that marked the beginning of the smaller Tovara waterway, a narrow channel into the mangrove swamp.

A White Ibis and (Stilt) Sandpiper kept each other company seeking bits of seafood in the viscous mud, but the Ibis sank much lower in the soft footing making its movements more sluggish.

We had been promised lots of bird sightings and were well on our way to drawing up a long list. A pair of Great Egrets stood out against the shade-darkened shore, one laying sprawled on the mud…

while its mate stayed close and stalked the shallows for perhaps a frog, snake or fish.

A Caspian Tern stood out against the dun-coloured sediment where full sunlight stressed the brilliance of its white plumage and large red bill…

whereas a Little Blue Heron kept to the shadows near the mangroves, both birds taking advantage of the unique habitat created by the slow-moving water.

When an Osprey appeared out of nowhere and soared above the river, I thought the Little Blue Heron was perhaps the wise one keeping close to the safety of the dense vegetation.

Bob and I soon realized that birds were not the only ones taking advantage of the rich aquatic life there in the river. It was a pleasant sight to see fishermen hauling in their nets and small fish glistening in the sunshine as some squirmed free.

Numerous Brown Pelicans lingered nearby and also benefited from the large schools of fish, often coming up with their pouches bulging.

In a quiet cove, another group of men were harvesting native mangrove oysters as they stood knee-deep and sometimes chest-deep in the cool water. The location provides the perfect conditions for oysters because the fresh mountain water flowing through the area provides constant irrigation. The banks and bed of the El Conchal Estuary are abundant with oysters so much so that anyone can go with a basket and harvest at their will.

Bob and I were experiencing a little bit of heaven on earth as we motored along the thick jungle shouldering both sides of the river. It was impossible to see through the dense foliage.

And then Chencho gently turned the motor, and the boat made a wide arc as it edged into the narrow channel that passes through the otherwise impenetrable mangrove swamp. I was so excited!

The sprawling, swampy mangrove is full of natural canals that flow through the jungle, but the overhanging branches must be hacked back to prevent them sweeping boaters overboard as they pass by. Like skeletal fingers, long, slender and pale, the slim roots reach for the watery surface then eventually gain a foothold in the rich sediment.

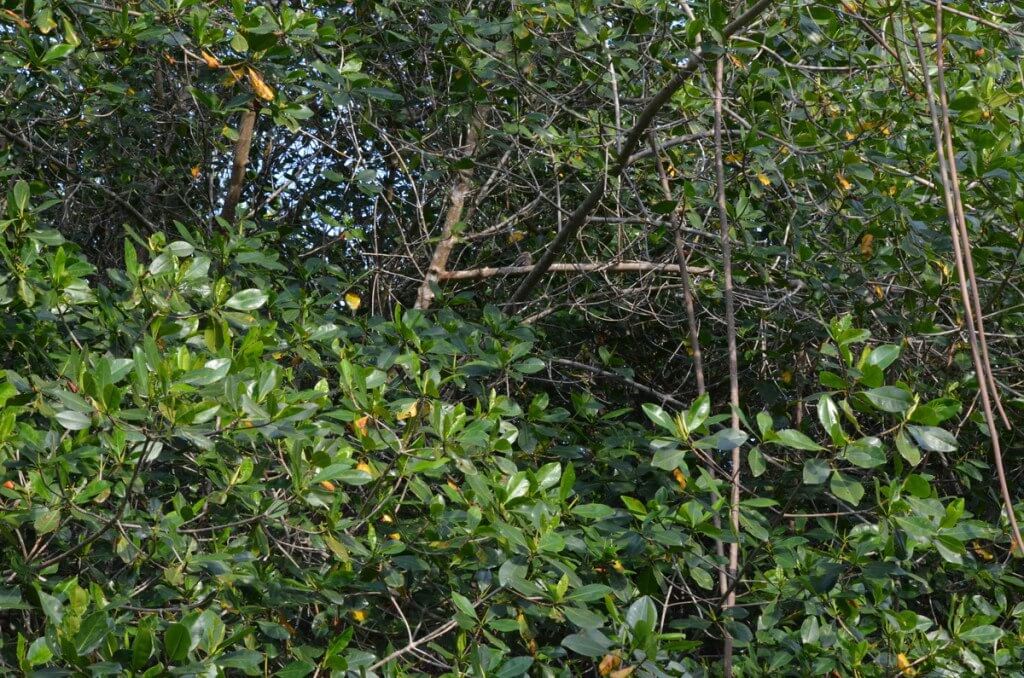

The edge of the open channel betrays the very, very overgrown habit of rooted mangroves that are virtually impassable, and the high water mark made it obvious that the tide was still out.

Often, it was Chencho’s keen eye that detected birds taking refuge in the thick foliage or foraging on narrow muddy banks in between all the roots of the mangrove trees as was the case when he pointed out this Yellow-crowned Night Heron. “Where?”, we exclaimed.

Chencho’s English was limited, and our Spanish is non-existent, but with patience, he idled the boat near the spot, putting the motor into reverse, and finally both Bob and I were able to locate the Yellow-crowned Night Heron where it slowly stepped in and around the tangle.

A second White Ibis was easily detectable because of its white plumage.

By times, the jungle closed in over our heads and we motored along beneath a long, winding tunnel of branches and leaves that blocked the sunshine and kept the sky hidden. It was really cool, literally and figuratively, and a welcome break from the otherwise hot and humid atmosphere in the swamp.

At its deepest and darkest point, the jungle would sometimes surprise us by allowing a stray beam of sunlight to fight its way through, and on one of those occasions, all three of us were delighted to see, quietly perched on a branch, a gorgeous male Green Kingfisher.

When a female Green Kingfisher revealed herself a little later on, she was not shown to such great advantage but was nonetheless a nice find.

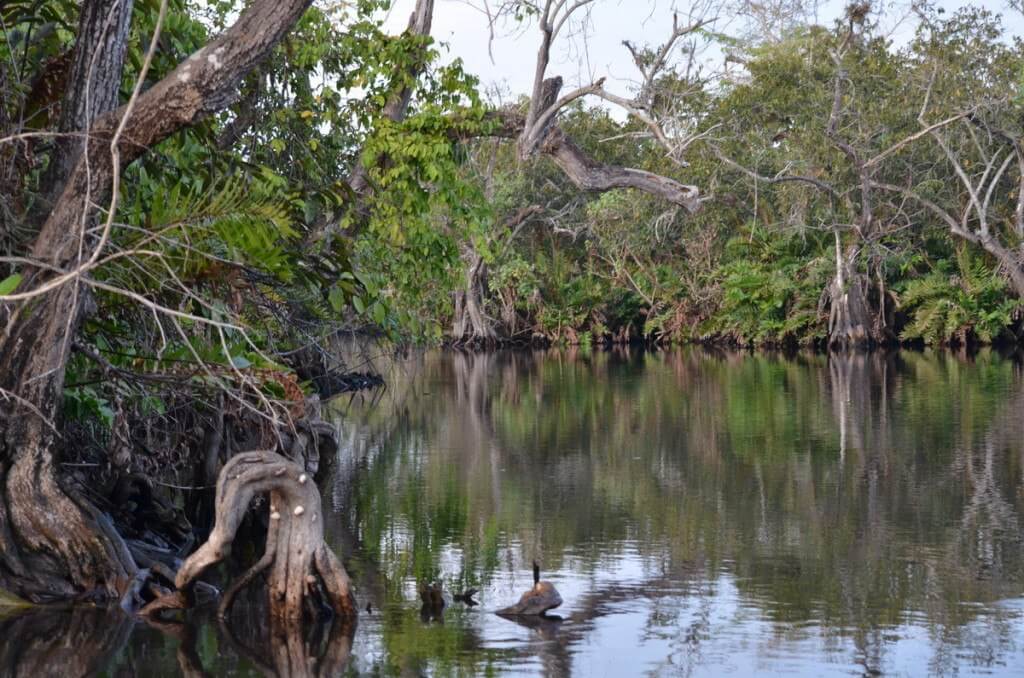

As Chencho navigated the channel through the swamp, Bob and I marveled at the beauty of the location. When we broke out of the tunnel of trees, bright sunlight allowed for lovely reflections on the placid water.

The open canopy existed in that particular spot because the channel passed beneath a bridge, and at the time, we thought nothing of it.

We instinctively ducked our heads as we cruised cautiously beneath the roadway. Later that evening, it would make for an interesting obstacle to our passage back through the jungle to the dock.

I was thrilled when we emerged on the far side of the bridge because I was the one to spot a Green Heron walking along a fallen limb in behind a screen of mangrove roots.

And we were extremely lucky when it decided to venture out of the thicket and take up a position out in the open…all the better for its foraging and my photography.

Up until that moment, Bob and I had had the twisting waterway all to ourselves, so when another boatload of tourists came revving towards us, obviously in more of a hurry than we were, all I could think was how it would frighten all the wildlife away from the water’s edge.

A few moments later, we found ourselves alongside a boat rental agency, the Embarcadero la aguado or the Watery Landing as it is called. It sits at about the halfway point along the sinuous passage through the jungle to La Tovara Spring, our final destination.

At the Watery Landing, the land between the channel and the highway is shared by La Tobara Restaurant & Bar that serves both motorists and boaters. Bob and I had driven past the business a couple of times in our car, and now its location was put into perspective.

Within a stone’s throw of the Watery Landing, Chencho slowed the boat to a crawl and pointed up into a tree thick with leaves and branches. At first neither Bob nor I noticed the bluish-grey rounded back of the Boat-billed Heron,

so Chencho adroitly maneuvered the bow of the boat in under the overhanging branches until we had a clear view. This particular species of heron is one of the most sought after by birdwatchers, and here we were within a few feet of it.

The afternoon was waning which might explain the Boat-billed Heron springing to life as we looked on. They are a nocturnal bird, and it seemed that this particular one was already attempting to trap insects in its over-sized beak. Over and over again, the Heron opened and closed its beak while sitting absolutely still, and we could see insects buzzing around its head.

Now, who could pick out this well-camouflaged Northern Potoo stretched out against a low slung tree branch? Why Chencho, of course. Aside from requiring his skills to navigate the complicated network of channels through the mangrove swamp, and operate the boat so that we were free to look around,

Chencho’s trained eye was indispensable when it came to finding the much-sought-after birds. Later in the evening, after it had grown dark, we were given the opportunity to observe a Northern Potoo as it prepared to hunt for food.

Bob and I were still in for more surprises. Unbeknownst to us, a trio of primitive wood and thatch homes stands on stilts and occupies one remote corner of a particularly wide section of the canal. The novelty of the buildings tickled our fancy and had us imagining life in simpler times.

Recreated for the filming of the 1991 Mexican film Cabeza de Vaca, these simple structures imitate those occupied by the earliest settlers to the San Blas area. I adored their whimsical charm yet wondered how the first settlers managed to survive in such rudimentary abodes.

Over the course of several hours, the atmosphere in the mangrove wetlands changed multiple times. The ceiling of clear blue sky enhanced our experience as the surroundings altered. Sometimes we were hemmed in by curved tree trunks or stout stumps…

and other times, the striking show of vibrant bromeliads, ferns and other marsh plants reflected in the still water painted a memorable portrait of the mangrove swamp for us to store in our memories forever.

As we slid past one stretch of the shoreline both Bob and I were struck by the intense fragrance of some delicate White Spider Lilies. It saturated the air and had both of us drawing long deep breaths to savour the perfume.

It seemed that things were changing quickly, and Chencho had picked up the pace of our progress, but still he managed to locate for us a Lesser Nighthawk that as of yet had not moved from its daytime perch.

You can see what I mean about requiring a trained eye because, from a distance, this Lesser Nighthawk was almost indistinguishable from the branch upon which it sat. All the regular guides have learned where the birds tend to frequent so they do have that knowledge in their favour.

As the sun dipped lower in the sky, there came a point where Bob and I just relaxed and watched the scenery pass by.

Nearer the final destination of our boat tour, La Tovara Freshwater Spring, Bob and I were surprised that the channel opened up, and we found ourselves bordered by vast marshlands on either side with a backdrop of hazy mountains already cloaked in fog.

A glance to the rear of the boat had us admiring a stunning orange-red sunset.

With darkness almost cloaking the land, myriad species of birds were flying in to roost for the night. A committee of Black Vultures had already settled into the upper fronds of a Palm Tree, dozens of Great Egrets were arriving in the mangroves from afar,

a Snail Kite was busily seeking its final meal of the day,

and one Yellow-crowned Night Heron that moments before had been sitting with its eyes closed was rudely awakened from its daytime slumber when the gentle pulse of our boat’s engine intruded on the solitude.

The fading rays of the sun cast a golden glow over the whole swamp even as Social Flycatchers and Tropical Kingbirds were frantically diving over the water to catch insects while there was still sufficient light.

Our boat tour did include a brief pause at La Tovara Freshwater Spring, but it was too late in the day to fully appreciate the crystal clear water of the spring that is the source for the waterway, nor did we take a swim there. I would not have been inclined to do so anyway given that at least one swimmer was attacked by a crocodile in that very location. We were rewarded with a look at a Limpkin, another species of nocturnal bird, but the wandering beams of light from Chencho’s torch combined with the gentle rocking of the boat made photography difficult.

We had heard other birdwatchers express disappointment at not finding a Northern Potoo…we had seen two already…and then Chencho’s searching rays found this one, wide-eyed and alert as it prepared to hunt, and also provided quick glimpses of numerous Pauraques as they darted through the night sky.

The return trip of 4 miles through the now totally dark swamp was eerie to say the least. Chencho used his LED flashlight to scan the water for crocodiles and in so doing lit up the edges of the channel very well. The result was that the dense jungle vegetation on both sides was perfectly reflected in the water before us. When it was time to pass back under the bridge, Bob and I had to lay almost flat on the boat’s seats because the high tide left barely enough room for even the boat to fit, and when unseen searching branches of the mangrove trees brushed our arms, it gave me the creeps. We unceremoniously drew up at the beach where we started and then Bob and I carried on our way. This had been a most extraordinary excursion and one we would not have missed for all the world.

Frame To Frame – Bob and Jean