A Tour of New Zealand’s Only White Heron Sanctuary

An opportunity to visit the only nesting site of White Herons in New Zealand could not be missed when traveling on the South Island near Whataroa. A day in advance, we booked ourselves on a tour that would take us to the heart of the Waitangiroto Nature Reserve to observe these elegant birds.

The morning of our planned excursion was overcast but dry. Allowing extra time to arrive in Whataroa from our lodgings in Franz Josef had Bob and me arriving at the offices of White Heron Sanctuary Tours at 10 a.m. for our 10:45 a.m. departure. Only hitch was two other couples that were running late.

Bob and I bided our time, growing more frustrated by the minute. Dion, the owners’ son, had promised to wait for the other passengers, but an hour later, he decided to pack us into his van and head off. At that precise moment, the other 4 people showed up.

It was a straightforward drive from Whataroa to get to the river where Dion would launch the jet boat. The distance of 15 kilometres took about 15 minutes.

Once at the specified location, Dion prepared to launch the boat in the Waitangiroto River.

All passengers were directed to a tidy building at the edge of the parking lot.

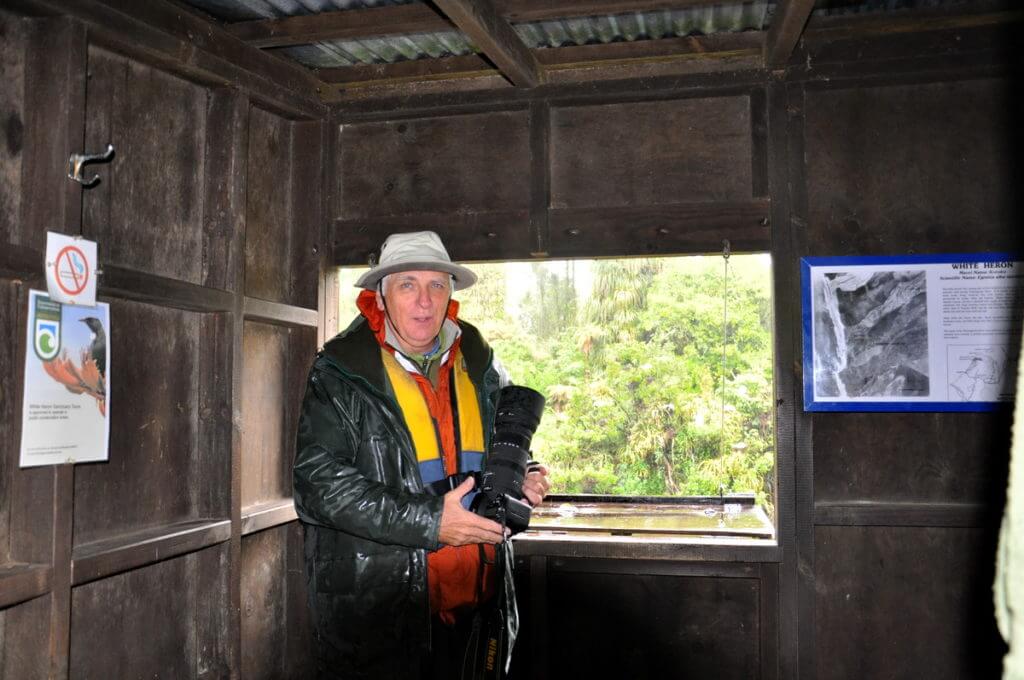

This staging building held all the rain gear for passengers about to embark on the boat ride. Because the weather can quickly change, we wore rainproof slickers and foul weather pants in addition to life vests.

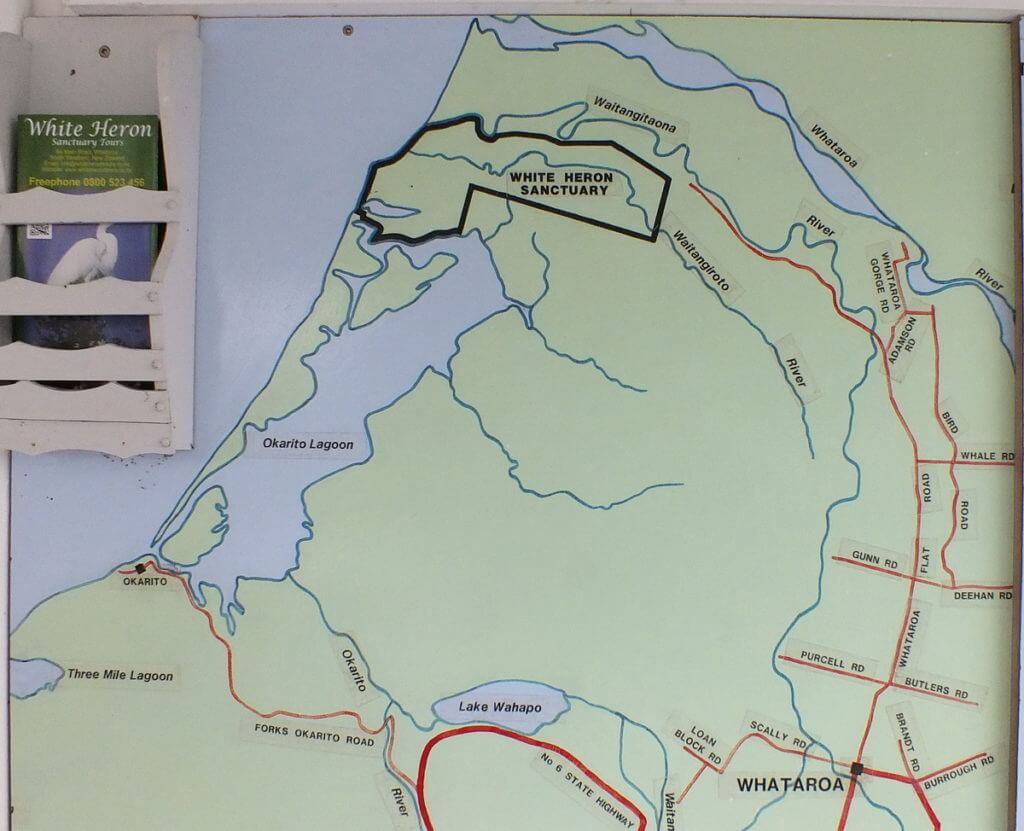

A map conveniently posted on the wall of the simple building showed us the location of the White Heron Sanctuary. White Herons, also known as Great Egrets and Kōtuku, are considered sacred by the Maori, so access to the Sanctuary is by permit only.

A raised boardwalk connected the back of the staging building to the bank of the river.

I was all set for the ride. Ready to help the passengers board, Dion slowly drew the boat up alongside the sturdy wooden deck.

Dion briefed us on what to expect as we sped downstream. It was a 12-kilometre ride that would take about 20 minutes at a speed of 30 kilometres/hour.

The Waitangiroto River is a broad flowing waterway that is very shallow. The speed of the jet boat kept the boat’s hull hovering on the surface as we peeled along.

Bob and I had opted for the back seats but what a mistake. It started to rain so we were not only battered by the wind but beaten by the driving rain.

It was an effort to keep the cameras dry but we were plenty warm.

The riparian habitat of the Waitangiroto Nature Reserve is a mix of dense rainforest dominated by ancient Kahikatea Trees.

Kahikatea Trees are coniferous trees endemic to New Zealand. They can live up to 600 years and achieve heights of over 200 feet.

Growing in lowland wetlands and forest, these trees were once heavily logged, and now less than 2% of the original Kahikatea Forest remains in New Zealand.

As we neared the breeding colony, White Herons were seen striding along the riverbank.

A docking area similar to the one where we launched facilitated disembarking from the boat at the end of the ride.

A short walk through the bush on a wooden boardwalk was necessary to reach the purpose-built viewing hide.

It was a wet walk through the gloomy rainforest, though less precipitation reached us below the canopy.

Bob and I took note of a small patch of Rainforest Greenhood Orchids along the trail.

The walk was not strenuous in the least, but I still took advantage of a lookout over the Waitangiroto Stream before we reached the bird hide.

The bird hide was constructed on stilts so that bird watchers could be at eye level with the nesting White Herons on the opposite side of the stream.

The Waitangiroto Nature Reserve was established in 1949 to preserve the natural nesting location and protect the rare White Herons.

White Heron Sanctuary Tours is a family-run business that has been operating for 30 plus years. Dion is a second-generation guide who works on behalf of the Department of Conservation to monitor the Herons.

From our perch in the bird hide, we could see 43 pairs of White Herons.

Back in December of 1865, this breeding colony was discovered by Gerhard Mueller, a pioneer surveyor tasked with surveying this area of South Westland.

Mueller was occasionally reduced to using a self-fashioned dugout canoe when exploring the waterways. When plying the Waitangiroto Stream, he happened upon a nesting colony of 50-60 White Herons just north of Okarito Lagoon.

White Heron feathers became fashionable in womens’ hats during the 1930s and 1940s, and to meet the demand, the Heron colony was almost wiped out. By 1941, only 4 nests were recorded at this spot.

It is thought that White Herons showed up here hundreds of years ago, blown off course across the Tasman Sea from Australia where they are widespread and abundant. Known as the Okarito Heronry, it has remained in essentially the same spot since before its discovery in 1865.

During breeding season, the White Herons feed in the large coastal lagoons including nearby Okarito Lagoon that Bob and I visited late the previous afternoon. No Herons were present at that time.

White Herons only inhabit this location during breeding season between mid-September and early March. They then disperse across New Zealand and are usually seen as solitary individuals.

By the time White Herons return to the breeding grounds in the spring, their appearance and plumage has been transformed.

The bill of a White Heron is normally yellow, but it turns a dull black, and the lores, that small patch of skin between the bill and the eyes, turn a vibrant shade of turquoise blue.

Spectacular long, lacy and elegant plumes have grown from their backs and wings and can be displayed much like a Peacock raises its tail.

Both male and female White Herons utilize the filamentous breeding plumes in their courtship displays. Males first select a nesting site, drive away all other birds then build a small platform upon which they can strut and advertise to the females.

Courtship displays are quite elaborate. White Heron males performing a Mating Dance will arch their head and necks upwards in a stretching motion while raising their nuptial plumes.

As the stretch culminates, the bill, head and neck remain pointed vertically, and the Heron bobs.

Then the head is lowered and the neck withdrawn.

If a male White Heron is defending his intended territory, he will erect his circular fan of plumage and sway from side to side.

Once a female White Heron shows interest in a particular male, they will preen each other and bow with entwined necks.

The Herons touch bills and clasp each others’ mandibles in a show of affection. We were so lucky to witness all these different steps in the courtship rituals of these Herons.

Once two White Herons pair up, they work together to complete the nest that the male began.

Long sticks and twigs are used to fashion the nest that is then lined with pliable plant material shaped into a cup.

Nests are built in the crowns of tree ferns that overhang the Waitangiroto Stream under the tall Kahikatea Trees.

When we visited the White Heron Sanctuary, some pairs of White Herons had 2-week old chicks, while other nestlings were several weeks old. We were delighted to spot one Heron that was tending her eggs.

Between 3-5 eggs are laid by a female, and both parents share the responsibility of incubating the eggs over the course of 28 days.

A nestling is fed partially-digested regurgitated food. The parents take turns foraging for fish and then feeding their young.

It would be around 8-10 weeks before the White Heron chicks fledge their nests.

Fledglings mature and are ready to return to the rookery for breeding 3 years later.

Bob and I were thrilled with the sight of the graceful, snow-white Herons in their natural nesting environment, but there was even more to appreciate at that location.

Sharing this ideal habitat is a small colony of Royal Spoonbills that put on quite a show of their own breeding plumage. More on that species in a separate post.

Also in extreme proximity is a Little Shag Rookery. The breeding success of all three species has been monitored since 1944 because they all put pressure on one another in such a small area.

Currently, the breeding population of White Herons in New Zealand is stable and numbers between 150-200 birds. Predators such as Stoats and Possums are trapped during breeding season to prevent breeding failure in the heronry.

With the White Heron or Kōtuku considered a symbol of things beautiful and rare, there is no wonder it holds a special place in Maori myth and folklore. To see one of these birds once in a lifetime is considered rare and a sign of good fortune.

Dion allowed us to remain in the bird hide for 40 minutes before ushering us back through the rainforest to the boat. It was difficult to pull ourselves away from such a sight.

Bob and I secured the front seats of the launch this time, and boy, were we glad. Precipitation started to pelt down heavier as we made our way upstream. It was the other passengers who faced the driving rain this time! We were protected by the boat’s windshield. What a glorious day!