Our Visit to the Pyramids of San Felipe de los Alzati

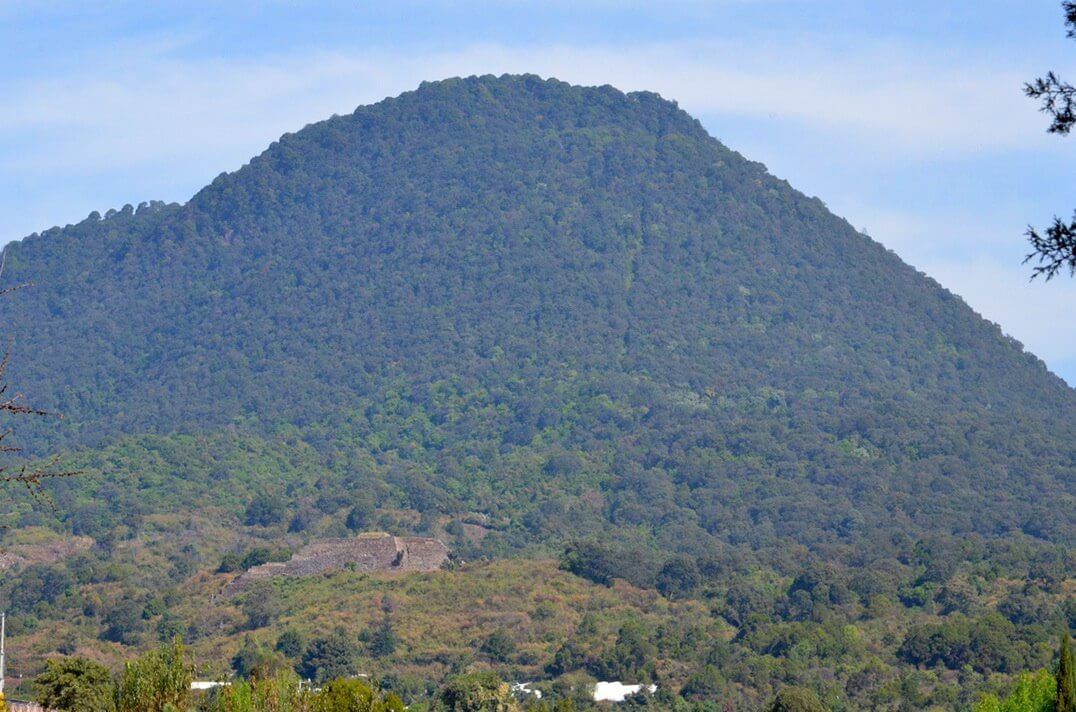

Two butterfly reserves down and one to go, so Bob and I decided to give it a break and check out the local pyramids. We were becoming quite familiar with Highway 15 being the main road in and out of Zitacuaro, and again we were headed northwest, this time in the direction of Tuxpan, Mexico. Our goal was the Pyramids of San Felipe de los Alzati just outside a small village of the same name. Long before we uncovered the secret trail to the pyramids, we saw them looming on a distant hill.

The ruins are located on the southern slopes, near the base, of Cerro Zirahuato. That beehive-shaped mountain peak tops out at 2,376 metres (7,795 ft) making it the 33rd highest mountain in the state of Michoacan, Mexico, and certainly could not be overlooked when searching the streets and backroads of the community for access to the pyramids.

Suffice it to say that road signs and markers are nearly non-existent in Mexico’s countryside and small communities, so after arriving in the village of San Felipe de los Alzati, over the course of an hour, Bob and I explored side roads and country lanes in search of some indication of how to get to the ruins. On the direction of one person, we followed a steep, narrow and very rugged dirt track before coming to a washed out section filled with baseball-sized rocks. We then knew it was time to get out of there, but Bob had to do so by backing the car down the steep incline. Thankfully, part way back to the main road, we saw a woman sweeping her front yard so inquired of her, with map in hand, and she pointed us up the road shown above. She graciously insisted that we park our car on her front yard and walk to the trailhead, which we did.

Suited up with backpacks containing our boxed lunch, water bottles, hiking sticks and hats, a mere 100 feet up that stony lane we found a series of stone steps that marked the entrance to an obscure trail.

Just the other side of the ancient stone wall was an empty field occupied by one lone horse, grazing as it was on sparse green grass. Archeologists, during their digs, discovered that an 18-hectare hub of ancient culture surrounded the pyramids, but this pastureland was not excavated. Of the 52 hectares encompassed by the whole Pyramids of San Felipe de los Alzati archaeological site, we wondered which of the neighbouring farm fields fell within its boundaries. I’m sure many hold secrets lying in wait to be uncovered and discovered.

Bob and I followed a cow path through the underbrush growing on the side of the mountain, and it was fraught with large rocks, displaced stones, even pieces of stonework from a wall that could be seen crumbling in under the dense thickets. It was not easy going.

There were absolutely no trail markers to guide us through the vegetation that towered over us obscuring any uphill view, and after having followed a number of erroneous side trails that promised an easier ascent, we came to a shaded copse neatly sheltering several beehives, and adjacent to that a compound of sorts protected by a 10-foot high chain link fence with a padlocked gate intended to keep out giants. We did not feel safe so retreated back down the trail to one ill-defined footpath that we had opted against earlier because it looked rather treacherous.

Of course, that short, steep slope littered with loose stones led us directly to the base of the Great Pyramid. You wouldn’t know it to look at it, but this ancient stone structure once stood mighty as the hub of a Matlatzincas native ceremonial centre.

Looking behind us from the flat area at the base of the pyramid gave us a lovely view of the farmland surrounding the archeological site but in no way reflected the arduous task of arriving there.

When I stood at the base of the towering staircase of narrow stone steps, I was determined to climb to the top even though I knew the descent would scare the heck out of me. To simplify the challenge, I mounted the narrow treads in a zigzag fashion, back and forth across the face of the staircase, so that the whole of my foot could be placed on each step. The reason the steps are so narrow is that the ancient people were shorter with smaller feet.

The steps were not in the best of repair so I found it necessary to focus on the gaps left by missing stones and loose pebbles on the treads in order not to stumble or slip. Once near the top, I established my balance and glanced at Bob far below.

That first flight of stone steps carried us up to the central plaza of the Great Pyramid, around which 5 structures had been constructed including this Lesser Pyramid. Rediscovered in 1963, only the two pyramids and square have been uncovered and explored to date.

It is believed that the structures were built by one of the ancient indigenous ethnic groups in the Toluca Valley around 600 A.D. Because the Aztec term for the Toluca Valley was Matlatzinco, any people who inhabited that valley came to be known as Matlatzincas regardless of which of the four native languages they spoke.

Numerous stones embedded in the walls of the pyramids had interesting carvings on them, depictions of ancient beings, gods or perhaps a tribute to the sun deity or astrological happenings.

Partially worn away by the elements, only some detail of the petroglyphs remains with lichens accenting the contours of the grooves.

The Lesser Pyramid lies to the north of the Great Pyramid and rises to about half the others height. Together with the other structures at that location, they originally served not only as a ceremonial centre but also as a lookout.

From the high vantage point afforded by the location and the summit of the Great Pyramid, it was possible to maintain surveillance of the surrounding valleys against invading forces of the Mexicas or Aztec armies. That is why the Matlatzincas were permitted to build on this site.

When studying the foundations of this pre-Hispanic ceremonial centre, as seen here in the Lesser Pyramid, one detects the influence of Teotihuacan cultures, which include the Otomi, Purepecha, Aztec and most notably the Matlatzincas who were considered part of the Purepecha Empire. The Purepecha or Tarascan Empire occupied most of the State of Michoacan at that time.

The dominant architectural style of the Teotihuacan culture is the slope-and-panel style, or stepped pyramid, with flat platforms on top of inward-sloping surfaces or panels. Each successive platform is smaller than the one below in order to achieve the completed geometric shape of a pyramid.

The upper platforms of the Great Pyramid rise from the central plaza and are accessed by another series of steps.

I was becoming quite adept at scaling the vertiginous stairway that would take me to the second platform of the Great Pyramid.

From the second platform or landing, I could look down on the Lesser Pyramid to my left, which you can see has very few steps leading up to its top platform or layer. There were three small tiers left to scale on the Great Pyramid, perched one on top of the other in the centre of the second platform, but each was represented by just one giant step up onto another stone layer.

I am standing behind one of four walls that delineates the topmost foundation. At one time, a wooden temple or perhaps one constructed of tiles would have been erected on top of this stone base. It is likely that ritual ceremonies were performed there being the most elevated and exalted location.

Feeling blessed ourselves, Bob and I seized the moment there on top of what is considered the largest pyramid in the State of Michoacan to unwrap our picnic lunch and savour the sweeping view of the Toluca Valley. A handful of young students had scrambled up the mountain only moments earlier, coming by way of the same trail that we had used, and now they jubilantly celebrated their quick ascent to the peak.

As we ate our sandwiches, a chilly breeze brought some respite from the scorching heat of the day. Surveying the pinnacle upon which we sat, Bob and I noticed that two Black Swallowtail Butterflies had joined us on the grass-covered rubble littering the top of the pyramid. All seemed right with the world at that moment.

After Bob and I completed our explorations, we retreated down the mountainside the only way we knew how. It was along the dusty road that Bob took notice of this hollowed out rock, an ancient remnant of the indigenous culture uncovered at this archeological site. It quite obviously was deliberately fashioned to serve a purpose, perhaps simply as a water reservoir. There was little information available at the site of the Pyramids of San Felipe de los Alzati, but we did learn that the main period of occupation was between 800-1200 A.D.

The horse was still standing idle in the pasture when I cast a backward glance at Pyramids of San Felipe de los Alzati, one of only seven archeological zones open to the public in the State of Michoacan. The pyramids are quite obviously still a work in progress as far as restoration goes, but it was nice to discover this historical aspect of the area in which we were spending so much time. An interesting side note is that, from the top of the Great Pyramid, we could see a building marking the official entrance to the historical site. It lay on the opposite side from which we had approached, but try as we might, on the drive back to our hotel, still no signage could be seen indicating how to find it. Asi es la vida!

Frame To Frame – Bob and Jean